A Cabinet of Curiosities

Fig. 0: ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’ in the De Lancey Room, RHN

For this month’s update, we proudly present our ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’ exhibition, a new permanent display of medical and scientific instruments from our archives which can be found in the De Lancey Lowe Room.

All of these objects, and many more, were collected by Dr Tony Sayer, one of our former GPs at the RHN. Colleagues remember with fondness his annual Christmas quiz, when he would retrieve some of his weird and wonderful items from their designated cabinet and challenge staff to try to guess what they were used for. Dr Sayer generously donated his entire collection to us when he left the Hospital.

We have undertaken some research around select objects and we are delighted to share our findings with you.

1. Irrigation syringe

Irrigation syringe

Item no. 009: A large barrel metal piston-action syringe engraved with “THE RANDALL-FAICHNEY CO. BOSTON U.S.A.”

Date: Circa early-twentieth century.

Use: Irrigation.

Fig. 1: Irrigation syringe, RHN Archive collection

Piston syringes date back many centuries. The first mention of using one to clear a blocked ear canal was in ‘De Medicina’ by Aulus Cornelius Celsus, written in the first century AD. According to his advice:

“If there is both a discharge of matter and a swelling, it is not unfitting to wash out the ear with diluted wine through an ear syringe, and then pour in dry wine mixed with rose oil, to which a little oxide of zinc has been added, or boxthorn juice with milk, or polygonum juice with rose oil, or pomegranate juice with a very little myrrh.”[1]

Soon after, the ear syringe mysteriously fell out of favour until the early-nineteenth century, although piston syringes were still being used in medicine to irrigate wounds and cavities. During this long span of time, people variously used little ear ‘scoops’ and ‘tongs’ to dig wax out – or poured liquids in, such as oils, spirits, and soaps, in an effort to soften and clear the wax.

Fig. 2: An ear-cleaner, attending to a man’s ear. Gouache painting by an Indian artist, circa 1825

It was French otologist Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard who, in 1821, resurrected the use of piston syringes for cleaning the ear canal, and this was swiftly adopted as the standard treatment. Today, the traditional irrigation method is still being used, along with the newer practice of microsuction.

The Randall-Faichney Company of Boston, Massachusetts, began life at the turn of the twentieth century as a manufacturer of automotive parts. It later began producing equipment for medical, dental, and veterinary uses, including various syringes, needles, and thermometers.

2. Glass bottle

Glass bottle

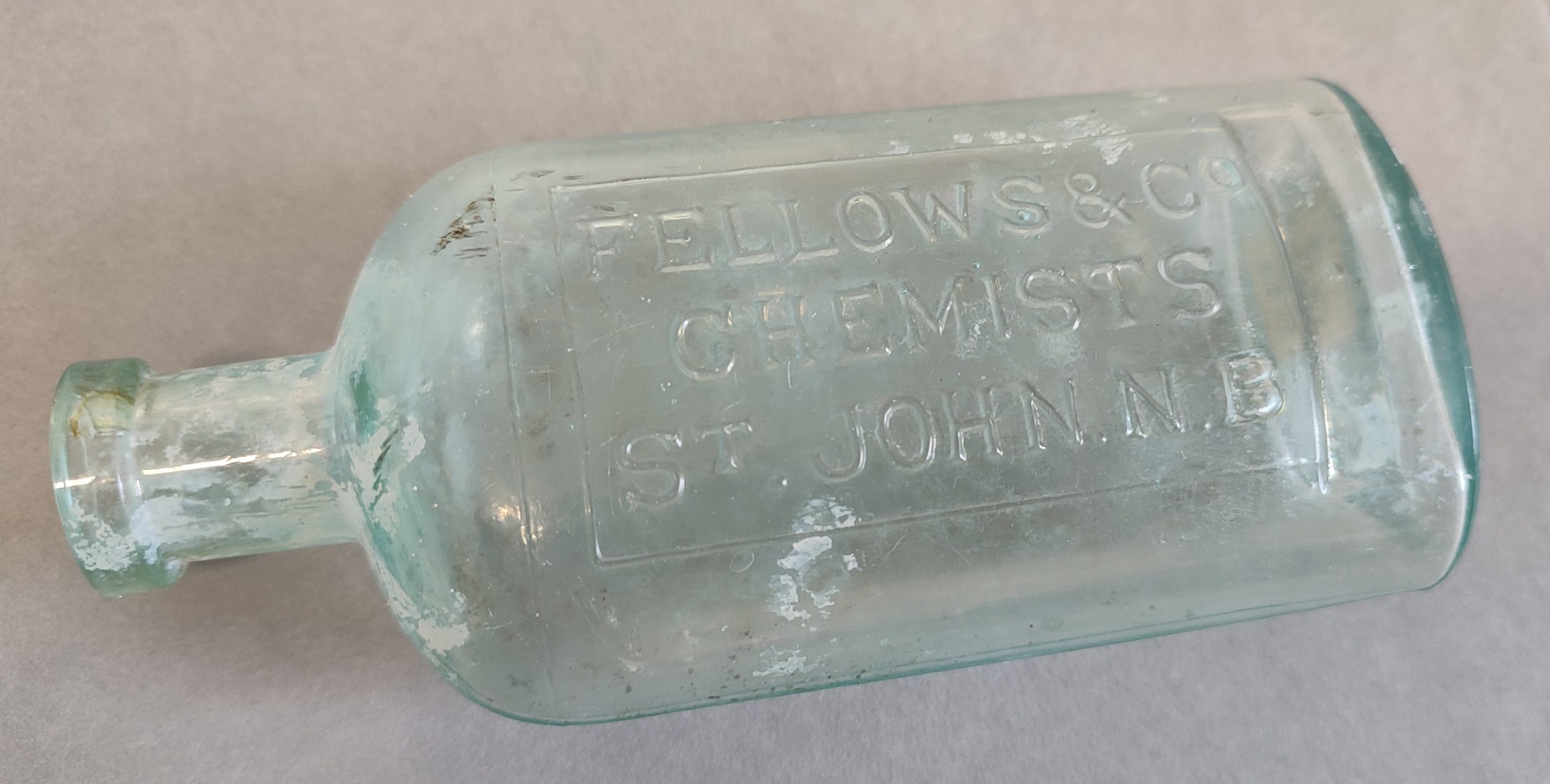

Item no. 008: A clear glass bottle embossed with “FELLOWS & Co CHEMISTS St. JOHN NB”

Date: Circa mid-nineteenth century.

Use: Liquid compounds, tinctures and other medicines.

Fig. 3: Glass bottle, RHN Archive collection

FELLOWS & Co was a chemist and druggist founded in New Brunswick, Canada, in the mid-nineteenth century. The company produced various patented household remedies with nebulous names, such as ‘Golden Ointment’, ‘Leemings’ Essence’, and ‘Speedy Relief’. In the late-nineteenth century, James Fellows himself concocted the formula for a new, self-named tonic: ‘Fellows’ Compound Syrup of Hypophosphites’.

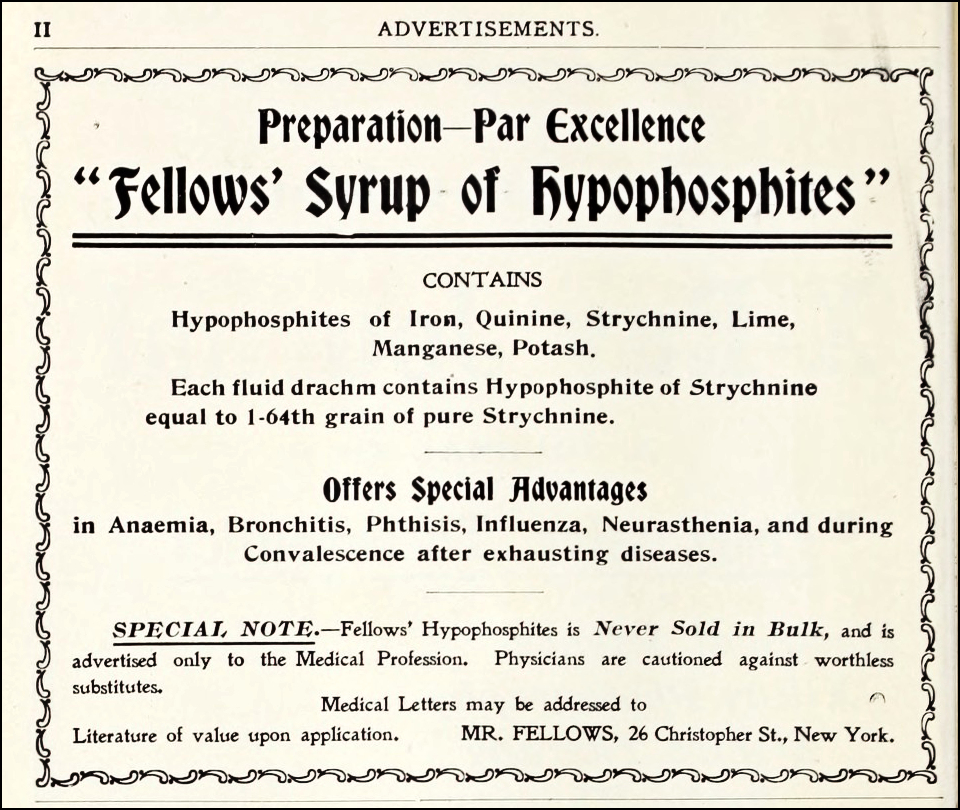

Fig. 4: Advertisement from The American X-Ray Journal, January 1904

Through shrewd use of advertising, his tonic became internationally popular both with physicians, who were encouraged to dispense it as a treatment for all kinds of ailments, and with the general public, who could also purchase the tonic over-the-counter in pharmacies. All this despite the fact that it contained Strychnine, a powerful nerve poison!

The mineral Phosphorus is essential to the body – especially for our metabolism, and for healthy bones and teeth. It was believed at the time that Hypophosphite broke down to deliver Phosphorus in the stomach, and was therefore an efficient and safe way to deliver the mineral to the body. Fellows’ Syrup contained small quantities of both Calcium Hypophosphite and Potassium/Sodium Hypophosphite.

Photographs of similar antique bottles still containing the ‘Compound Syrup’ show a very dark viscous liquid.

3. Ceramic phrenology head

Ceramic phrenology head

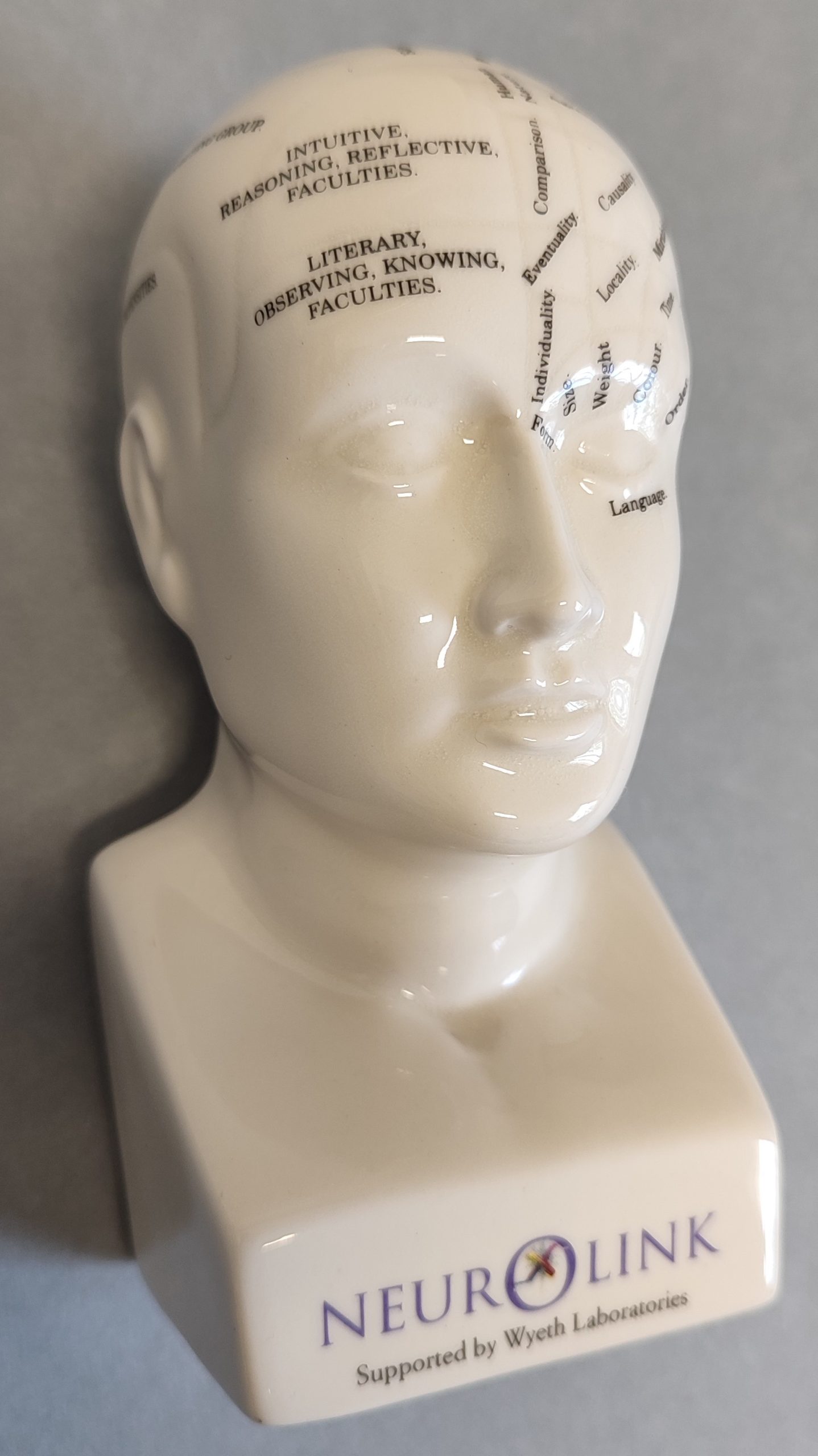

Item no. 018: A ceramic phrenology head – a promotional item for Neurolink ‘Efexor Venlafaxine’ (stamped on the rear)

Date: Circa mid- to late-twentieth century.

Use: Promotional item.

Fig. 5: Ceramic phrenology head, RHN Archive collection

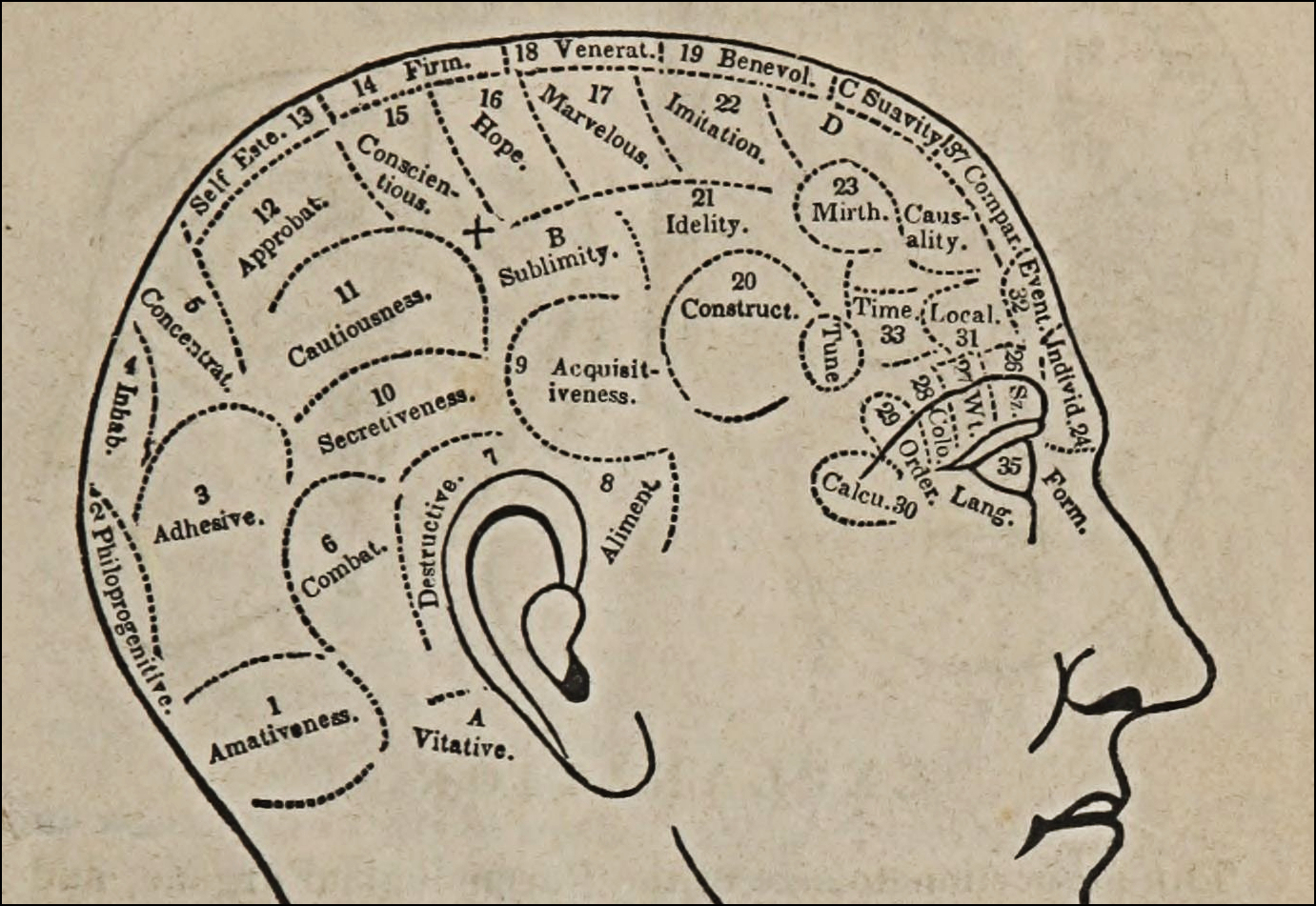

Phrenology grew out of the theories of Viennese physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), who believed that the brain was composed of numerous separate regions, or ‘organs’, each of which exerted an influence over a person’s behaviour and personality. When performing a ‘skull reading’, Phrenologists would refer to annotated heads such as this one, and would purport to determine the character, nature, and appetites of a patient by feeling and measuring their head.

Fig. 6: Phrenological chart, presenting an outline of phrenology. J.N. Bang, 1841

Although it may seem a rather eccentric and harmless pseudoscience today, the history of phrenology has a darker side. In the early-nineteenth century, these types of physical observations and measurements were used to validate the supremacy of the white male – and thus to justify slavery, sexism, and other prejudices.

Efexor Venlafaxine is a ‘serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor’ (SNRI) class antidepressant medication used to treat a number of depression and anxiety disorders.

4. Hearing Aid

Hearing Aid

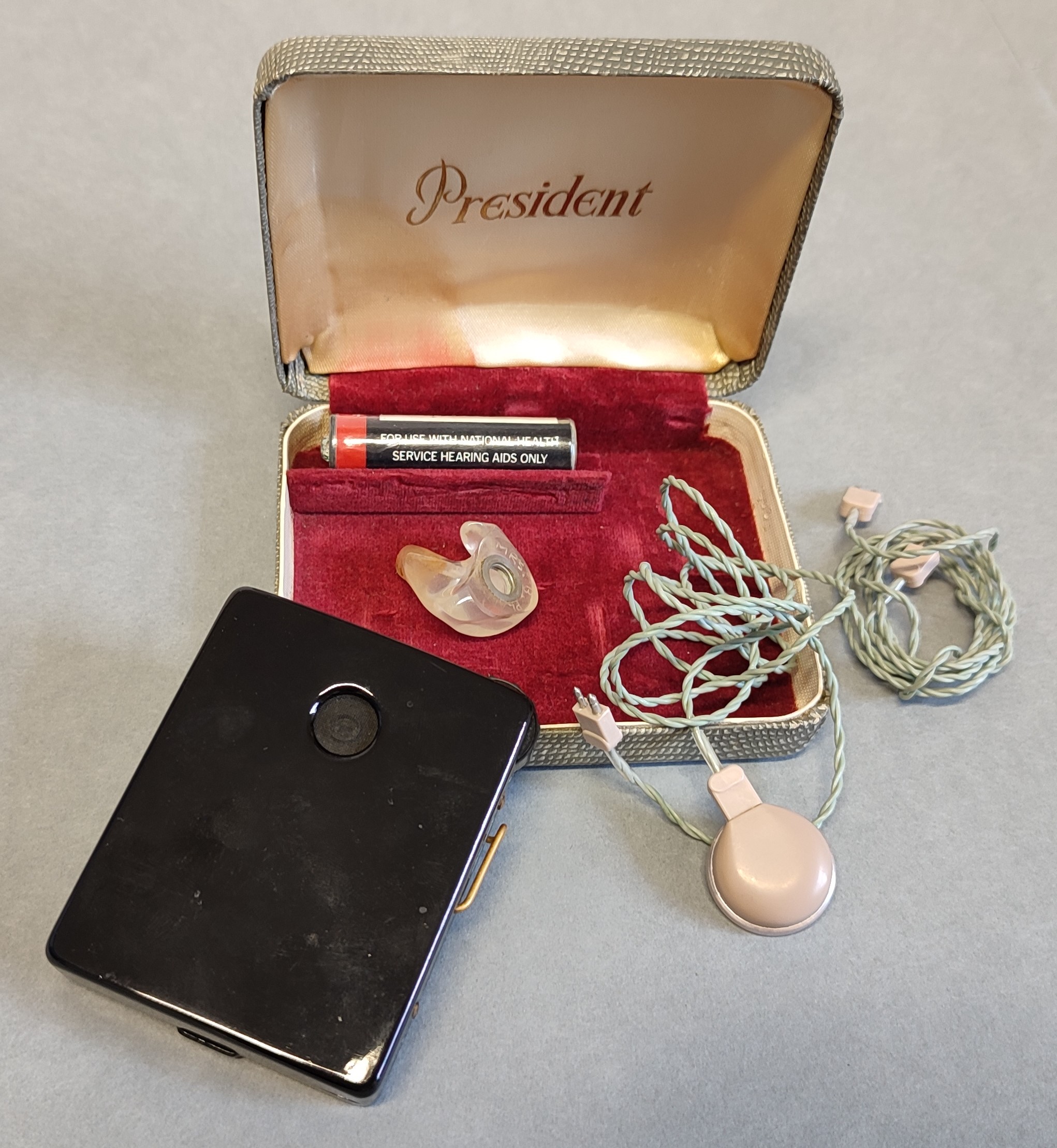

Item no. 015: Ardente ‘President’ hearing aid (transistor, earphone, earmould, 2x cables, battery), in hinged box.

Date: Circa 1950s or 1960s.

Use: Hearing aid.

Fig. 7: Ardente ‘President’ hearing aid, RHN Archive collection

There is evidence of hollowed out animal horns being used by people with hearing loss at least as early as the thirteenth century. The first purpose-made ear trumpets – which were made in all sorts of designs and from different materials – came along in the mid-seventeenth century. But it wasn’t until 1800, with the invention of Frederick C. Rein’s collapsible ear trumpet, that they began to be commercially produced. Over the course of the following one hundred years, the popularity of hearing aids blossomed, more manufacturing firms were created to meet this increasing demand, and a plethora of different designs and models became available.

Fig. 8: A woman shouting into a man’s ear-trumpet. Wood engraving, 1883

Following the invention of the telephone in the 1870s, hearing aid technology was revolutionised. This began with the development of early electronic hearing aids; and then, in the 1920s, of vacuum tube hearing aids; and, in 1948, of the first transistor hearing aid, developed by Bell Laboratories.

These last remained in use until the late 1980s, when digital chips capable of high-speed digital signal processing made it possible to commercially produce full digital hearing aids. Because digital hearing aids convert sound waves into binary information, they can be programmed to minimise acoustic feedback, amplify speech, and reduce background noise.

Ardente was founded in 1919, initially as a retailer of imported hearing aids. It soon began to manufacture its own models of hearing aid, however, as well as other sound amplification devices, such as radios, intercoms, and speakers. Writing about advertisements for a similar Ardente hearing aid from the 1960s, Enrika Pavlovskyte highlights a critical concern in the choice of terminology which would have been prevalent at the time:

“While their advertisements addressed customer concerns, they also worsened misrepresentation of D/deafness. Such expressions as “relief from deafness”, “comfort and concealment”, “like those with normal hearing” emerge in some of their promotional materials. These statements reflected and reinforced the widespread opinion of D/deafness as an abnormality that had to be fixed or hidden.” [2]

5. Atomiser

Atomiser

Item no. 021: Devilbiss Atomiser.

Date: Circa early- to mid-twentieth century.

Use: Medication delivery in the form of a spray.

Fig. 9: Atomiser, RHN Archive collection

The first atomiser was developed in 1887 by the American otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat doctor), Dr Allen DeVilbiss (1841-1917). Initially, it was used to coat the throat and nasal cavity with a numbing solution of dissolved cocaine. It was very quickly adopted for administering all types of liquid medicines. Allen’s son, Thomas DeVilbiss, would later adapt his father’s design to atomise perfume.

According to its own instructions, this atomiser could be used for “Oils or Aqueous Solutions”:

“Since many serious illnesses start in the nose and throat, it is a sound preventive measure to spray the nose and throat regularly with a prescribed or approved solution in an atomizer. With the atomizer, the solution reaches even the most remote regions of both the nose and throat, regardless of posture.”

You can see actor Joel McCrea use a very similar atomiser in the film ‘Sullivan’s Travels’ (Paramount Pictures, 1941).

Fig. 10: Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake in ‘Sullivan’s Travels’, 1941

6. EXTEROL Medical Tuning Fork

EXTEROL Medical Tuning Fork

Item no. 020: EXTEROL Medical Tuning Fork.

Date: Circa mid-twentieth century.

Use: Testing hearing (primarily).

Fig. 11: Medical Tuning Fork, RHN Archive collection

Medical tuning forks are primarily used to test for hearing loss. But in the absence of an X-ray, they can also confirm a suspected bone fracture. And they are even used therapeutically, where their fixed-tone soundwave can help patients achieve a deeper state of relaxation.

Sound can reach our ears through ‘air conduction’ – hearing which occurs through air near the ear – and ‘bone conduction’ – conduction through vibrations via bones. The Rinne test and the Weber test are two simple tests for doctors to detect conductive hearing loss using a tuning fork. Although they are simple, these tests can help to identify a number of different causes of hearing loss, including: eardrum perforation; wax in the ear canal; ear infection; middle ear fluid; and nerve injury to the ears.

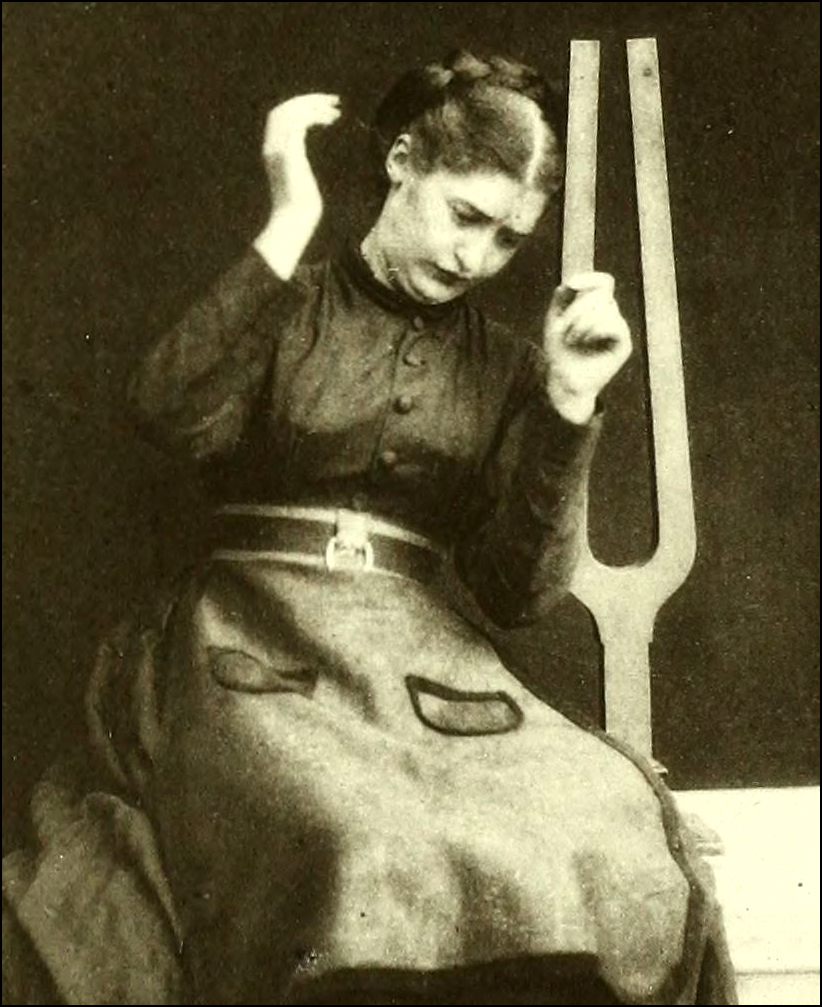

Tuning forks have a more colourful medical history than you might imagine. In the late-eighteenth century, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) conducted a number of experiments involving acoustic stimuli on his patients. He was particularly interested in what was then a common diagnosis of ‘female hysteria’, and in using hypnosis to treat that condition. He discovered that tuning forks could help to induce what he termed a ‘cataleptic’ (by his definition, akin to hypnotic) state. In other experiments, he used a giant tuning fork to create a resonating chair.

Fig. 12: ‘Catalepsy provoked by the sound of a tuning fork’, circa 1877

Charcot himself described the effect of this treatment:

“The patients are seated over the sounding box of a strong tuning fork, made of bell metal, vibrating 64 times in a second. It is set in vibration by means of a wooden rod. After a few moments the patients become cataleptic, their eyes remain open, they appear absorbed, are no longer conscious of what passes around them, and their limbs preserve the different attitudes which have been given them.” [3]

Yet another medical use for the tuning fork was in identifying possible fractures. In the April 1904 edition of the medical journal ‘The Doctor’, we find a fascinating description of how this test should be carried out:

“The test is made by placing the bell of a stethoscope, over the bone, near the supposed fracture, where the soft tissues are as thin as possible, and the handle of a tuning fork as close to the bone as possible beyond the supposed seat of fracture. The sound will be transmitted through the shaft of the bone to the stethoscope and through the stethoscope to the ears of the examiner. When the bone is intact, if the test is properly made, the sound of the fork will be heard with great distinctness; but if there is a lack of continuity, the sound will either not be heard at all or will be heard very faintly. By comparing the intensity of the sound on the suspected side with the sound heard under similar conditions on the normal side, the question of continuity of bone can be determined. The test for fractures is based upon the fact that bone is an excellent conductor of sound waves, while the soft tissues of the body conduct sound waves very poorly.” [4]

7. Silkworm Gut

Silkworm Gut

Item no. 019: ALLEN & HANBURYS Ltd Silkworm Gut. Strong. In cardboard box.

Date: Likely circa 1880-1920.

Use: Sterile silkworm gut sutures, used for the temporary stitching of wounds.

Fig. 13: Silkworm Gut in box, RHN Archive collection

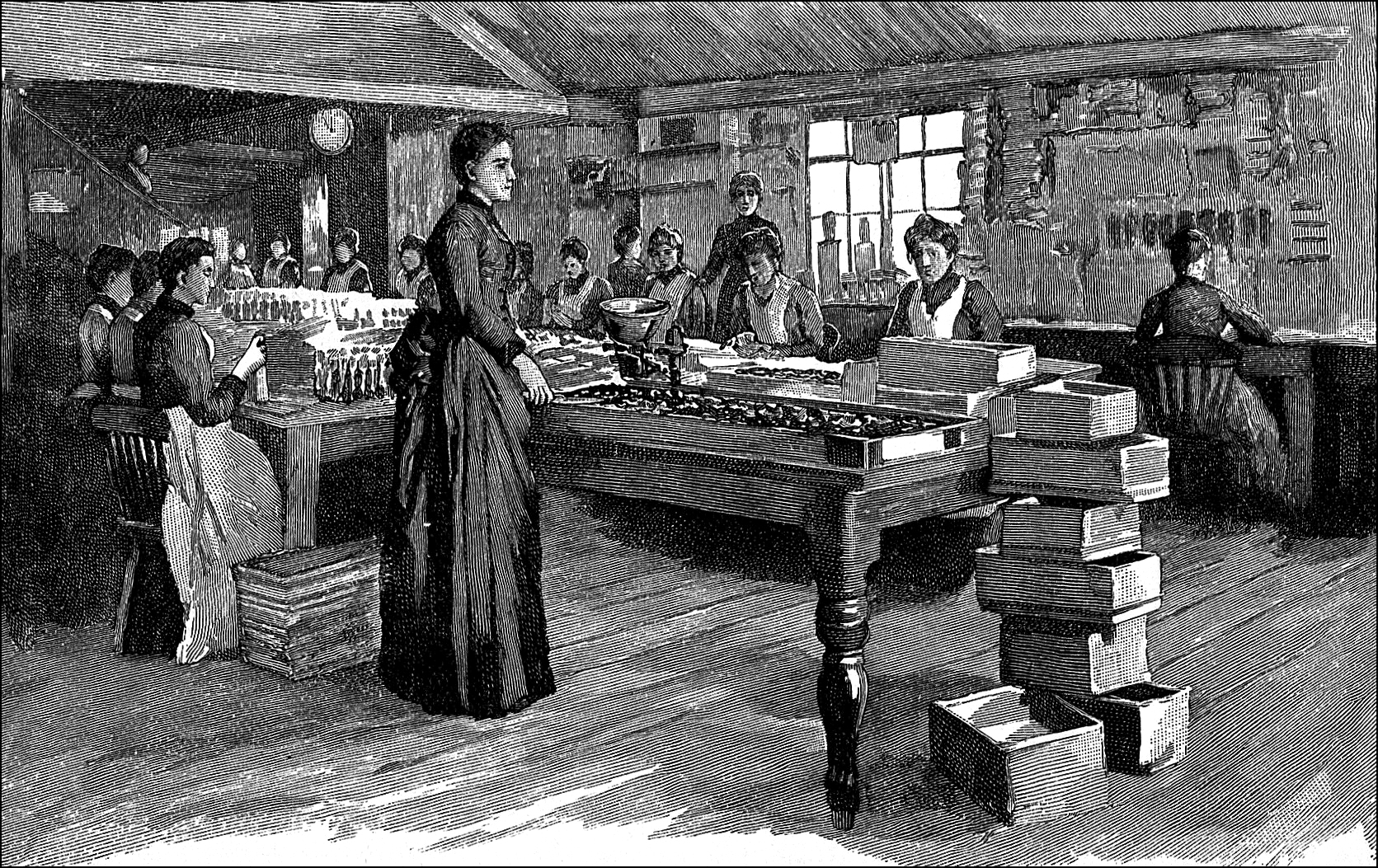

Allen & Hanburys Ltd. began life as a small pharmacy business founded in 1715 by Silvanus Bevan (1691-1765), a Welsh apothecary and Quaker, in Lombard Street in London. In 1792, scientist, and fellow Quaker, William Allen became the company’s clerk. Soon rising to become a partner in the business, he eventually took it over entirely. In 1808, William’s nephew Daniel Hanbury also joined the company, followed later by his cousin Cornelius Hanbury and, in 1824, the business was renamed ‘Allen and Hanbury’.

Fig. 14: Interior of Allen & Hanbury’s general packing room, 19th Century

Moving into the second half of the nineteenth century, the company expanded with new specialist factories. Here, they developed milk foods for infants, dietetic products, malt preparations, and dozens of different pastilles. In the 1870s, they were one of the first companies in the country to produce cod liver oil. According to published advertisements, their product was “as nearly tasteless as Cod-Liver Oil can be”, and “no nauseous eructations follow after it is swallowed” [5]. In 1878, they also began to manufacture surgical instruments and other medical products. In 1958, the company of Allen & Hanburys was absorbed by Glaxo Laboratories.

The use of sutures to close wounds dates all the way back to ancient civilisations, when people made use of the materials which were available to them at the time. There is evidence that Greeks used horsetail hair threaded through bone needles, and that Egyptians used linen, at least as far back as 3000 BCE. The suitability of a suture material is assessed based on a number of different characteristics, including: absorbability; visibility; breaking strength; ease of handling; and tissue reactivity. [6]

Silkworm gut is a non-absorbable surgical thread used for the temporary stitching of wounds. Silk as a material is strong, and offers excellent handling to tie secure knots, but – due to it being derived from an organic substance – it is more prone to provoking an inflammatory reaction in tissues.

Fig. 15: Women in a garden sorting silkworm eggs for incubation, 1749

In the ‘Postgraduate Medical Journal’ of October 1949, A.M.C. Humphries provides us with a characterful introduction to the manufacture of silkworm gut:

“In the preparation of silkworm gut the caterpillars on reaching maturity are not allowed to spin their cocoons. The peasant, who has so tenderly cared for his charges up to this point, suddenly turns traitor and rudely dumps them into a vinegar bath, putting him within reach of his goal but putting the caterpillars for ever beyond reach of theirs. The viscous sticky fluid, which would harden upon coming into contact with air into the strong glossy thread of silk, is prevented by the vinegar bath from being spun into a cocoon, and a peasant girl with deft fingers extracts the tubes and lays them across her knees, stretching them to their full length. Silkworm gut, even to this day, is almost exclusively produced in the location where it had its inception some 60 or 70 years ago – the city of Murcia, capital of a sunny province of the same name in south-easterly Spain.” [7]

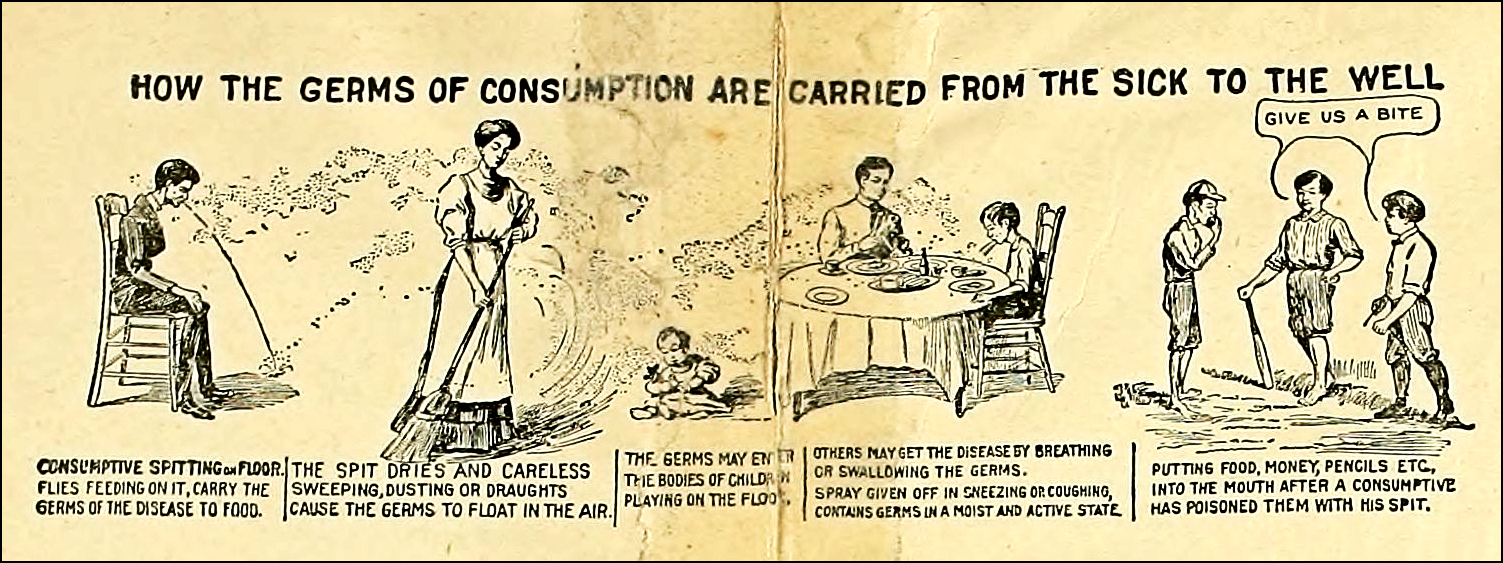

8. Yellow metal sign: PREVENTION OF CONSUMPTION

Yellow metal sign: PREVENTION OF CONSUMPTION

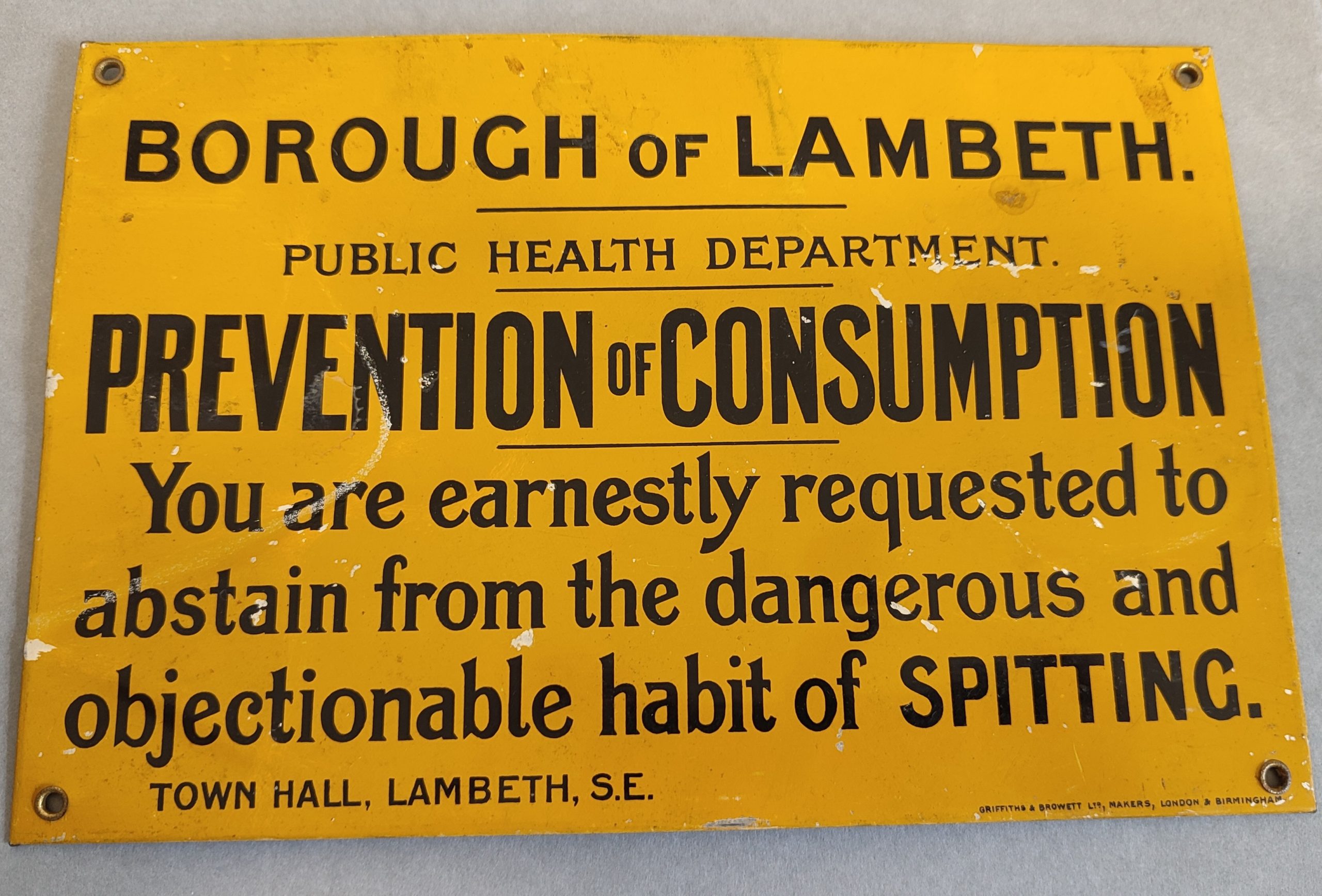

Item no. 011: Yellow metal sign: PREVENTION OF CONSUMPTION.

Date: Circa early- to mid-twentieth century.

Use: Warning sign.

Fig. 16: PREVENTION OF CONSUMPTION enamel sign, RHN Archive collection

Tuberculosis (TB) was one of the biggest killers of the nineteenth century. In the early-twentieth century – once it was understood that it was a bacterium, and that coughing or spitting spread the disease – signs such as this one were erected to try to prevent the spread of infection. The later stages of TB became commonly known as ‘consumption’ because patients wasted away to such an extent that it looked as though they were being ‘consumed’ by the disease.

Fig. 17: Page from the leaflet: ‘How to avoid consumption (tuberculosis)’, 1909

9. Shoe shine brush

Shoe shine brush

Item no. 022: Shoe shine brush.

Date: Likely circa early-twentieth century.

Use: Applying polish to, cleaning, and buffing, shoes and boots.

Fig. 18: Shoeshine brush, RHN Archive collection

We weren’t sure exactly what this brush was used for until we spotted one just like it being used to put a shine on a boot in the 1936 film ‘A Tale of Two Cities’.

Fig. 19: Donald Haines (l) and Billy Bevan (r) in ‘A Tale of Two Cities’, 1935

Objects such as this one serve to remind us of the manifold practicalities – large and small; everyday, extraordinary, and specialist; medical, therapeutic, and domestic – which go into administering a hospital such as the RHN.

Written by Dr Sarah E Hayward, freelance historical researcher and heritage assistant, and volunteer at the RHN archives.

References

1] De Medicina by Celsus W. G. Spencer, ed. (trans.) Cambridge, Massachusetts. Harvard University Press. 1971 (Republication of the 1935 edition), p.237

[2] Enrika Pavlovskyte, ‘The Duchess hearing aids’, Museum of Medicine and Health, 2021

[3] Carmel Raz, ‘Of Sound Minds and Tuning Forks: Neuroscience’s Vibratory Histories’ in ‘The Science-Music Borderlands’, edited by Elizabeth H. Margulis, Psyche Loui and Deirdre Loughridge (The MIT Press, 2023), p.115

[4] The Doctor Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Therapeutics, Vol. XIV (April 1904), p.26

[5] Advertising (1885, June 20). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 – 1912), p. 1316

[6] Bret R. Baack MD et. al. ‘Suture Material’ Dermatologic and Cosmetic Procedures in Office Practice, 2012, Pages 37-45

[7] A. M. C. Humphries, ‘The Story of Silk and Silkworm Gut’ Postgraduate Medical Journal, Volume 25, Issue 288, October 1949, Pages 483–488, p.484

Images:

Fig. 2: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark (591183i)

Fig. 4: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 6: Wellcome Collection. This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.). Public Domain Mark

Fig. 8: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark (12120i). From The Comic Annual by Thomas Hood, 1883

Fig. 10: Preston Sturges (director), ‘Sullivan’s Travels’ (Paramount Pictures, 1941)

Fig. 12: Bourneville et P. Regnard, ‘Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière : service de M. Charcot’ Public Domain Mark, p.205

Fig. 14: Allen & Hanbury, general packing room. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Fig. 15: Textiles: women in a garden sorting silkworm eggs for incubation. Engraving by B. Cole, 1749. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark (43589i)

Fig. 17: How to avoid consumption (tuberculosis) This material has been provided by the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University Libraries/Information Services, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University. Public Domain Mark, p.7

Fig. 19: Jack Conway (director), ‘A Tale of Two Cities’ (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1935)