Cat’s meat sellers, wheelwrights, and steamboat mates

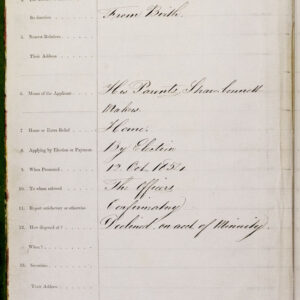

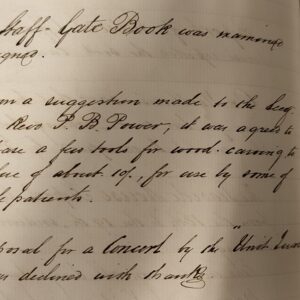

Fig. 1 The first entry from the hospital’s admission case books, 1854

This month, we’re privileged to hear from some of our delightful archive volunteers who’ve been committedly uncovering unexpected details about our patients from our first admission case books. These case books not only reveal information about the occurrence of archaically-titled diseases – what, for example, is a “rodent ulcer”? They also tell us about the social circumstances of our earliest patients, ie. what they did for a living, who cared for them prior to their admission, and how they dealt with their chronic illnesses or disabilities in a world where there was not much provision for these types of conditions.

It’s not always easy reading, and we commend our archive volunteers for patiently transcribing the elaborately-formed nineteenth-century script for us to access and utilise the historical data for generations to come.

Fig.2 Cats and Dogs’ Meat, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1820

Fig.3 Wheelwrights, by Marechal Grossier, 1769

Fig.4 Steamboat Ben Campbell, unknown, 1852-1860

Carl's story:

Since this summer, I’ve been transcribing entries from the 1897 admissions register. I got involved because I love archives and history, and the work of the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability neatly intersects with my role working as a librarian in the health/medical sector.

I must say that it is a real privilege to be doing this transcription work as you briefly encounter the lives of candidates seeking to be a pensioner or inmate of the Hospital. The information found in the admissions registers provides fascinating insights, revealing stories, and a wealth of detail. I’d like to share some of those with you now.

First up, proportionally, I’d say that slightly more women than men apply, and certainly more single people do compared to married or widowed ones.

Whilst you’d expect many applicants to reside in and around London, many others come from all over: Brighton, Bristol, Hereford, Ipswich, Kirkcaldy, even Guernsey. No one yet living in Wales or Ireland has appeared in the 1897 register.

I’ve encountered in the records many different medical conditions, diseases and “afflictions”, and would add that consequently my awareness has grown in equal measure to my compassion levels. What is noticeable are the small number of physical disabilities that now may not be or are no longer debilitating, because they are now managed through medication and/or surgery. A fair number of applicants were born with their conditions. Some have acquired them, presumably from their unsafe, unhealthy occupations and workplaces. Compared to today, surprisingly perhaps, almost all of the record descriptions portray physical conditions; it is very rare to find an account of someone who has exclusively mental or neurological conditions.

Equally moving, is the information relating to how the individuals are managing and surviving economically. It is really good to see and to know that there are family, friends, trades clubs and charitable societies supporting them financially, with work, homes, comfort. Some applicants are employed in permanent or more likely occasional work – dressmaking, needlework, housekeeping, colouring photographs, working in stables.

I find the diversity of occupations really interesting and insightful as it paints a broad, busy and global picture of Britain and its Empire as it approached the twentieth century. Many jobs are instantly recognisable and exist today – labourers, stonemasons, farmers, tailors, dressmakers, doctors, painters, policemen, cooks, religious Ministers, booksellers, grocers, shopkeepers, soldiers, school staff, and the unemployed. Some are much rarer these days, or arguably even obsolete – butlers, parlour maids, furriers, wheelwrights, coachmen. There are also mariners, tea traders, railway clerks, engine drivers, engineers, journeymen, telegraph messengers, all familiar faces in the late Victorian society.

Inevitably, it is very hard not to feel disappointed and saddened when a candidate is “declined as unsuitable”, although understandable given the finite resources available to support or care for them. Regarding the unsuccessful candidates who don’t secure a pension or get admitted as an “inmate”, I am often left wondering what happened next to them, how they coped, who was there to help. Naturally, it’s a great relief when the individual has been successful. Then I think how brilliant that the Hospital existed then, as it does now, as a safety net for the vulnerable in society in need of the best medical and nursing care.

I would wholeheartedly recommend you find out about getting involved in the transcription project.

Carl Banks

James' story:

One of the most interesting parts of transcribing the casebooks has been the wide variety of conditions the applicants were experiencing. Despite the hospital’s name, many people who applied did not have neurological problems, with some of the most common conditions being Bronchitis (an inflammation of the lungs), Rheumatic arthritis (a form of arthritis which affects the joints), gout and scarlet fever.

Many of the conditions the patients were suffering from are now known by different names. This includes Disseminated Sclerosis (Multiple Sclerosis), Progressive Muscular Atrophy (Duchenne’s) and Lateral Sclerosis (ALS.) Some of the conditions have very unusual names, such as a “Rodent ulcer”, a term which refers to what is now known as Basal Cell Carcinoma.

Overall, I have enjoyed learning about how these disorders and medical terminology referring to them has changed since the late Victorian period.

James Denny

Kirsty's story:

In transcribing the RHN admissions case books, I have been amazed by the extraordinary wealth of social history they contain. Every page offers a vivid snapshot of the health, finances and family ties of chronically ill, impoverished men and women in nineteenth century Britain. The wide range of health conditions which led them to seek the hospital’s support included paralysis, epilepsy, rheumatism and other chronic illnesses. Many suffered with long-term debilitating symptoms resulting from infectious diseases, whilst others lived with permanent injuries from the physical demands of labour in this increasingly industrialised age.

One applicant was a railway porter who had suffered a spinal injury from ‘being crushed between two railway trucks when engaged in shunting’; another was a steamboat mate, left with paraplegia after an injury to his spine ‘from a broken hawser [cable] when on board a tug’. The case books are filled with men and women who had enjoyed previous economic security, often in skilled trades. Unable to work due to poor health, the applicants survived on meagre savings, small pensions from previous employers, allowances from charitable organisations and occasional odd jobs. Most relied on elderly parents or working children, networks of extended kin or friends for financial support. One applicant was dependent on a 78-year-old cousin, another received a weekly allowance from her late husband’s brother. The records also offer a vivid, sometimes brutal, view of women’s domestic lives. In 1895 Susan Wall applied to the hospital for a pension, suffering with paralysis in her right hand after her husband ‘cut her throat when mad’. She received a pension from the hospital until her death four years later, aged just 31. The case books reveal so much about the applicants’ lives and the world they lived in, and I am glad to help make them more widely accessible through this transcription project.

Kirsty Walker

NJP’s story:

I have been transcribing the casebook for applicant entries in the late 1800s. These months have been an incredible journey into the past! Due to the nature of many of the ailments presented in the casebook, I have spent a lot of time on research regarding medical terminology and treatments and the civil development of London pre-World War I. By the time I had completed my 50th entry, I realised I had also developed a curiosity for the social perceptions on certain medical disorders, and I wanted to know more about the thought process behind the decisions made by medical professionals concerning the numerous cases of rheumatic disorders. Many of the entries do not bear explicit notes on why an applicant would have been turned away as ‘not sufficient urgency’, so I have enjoyed carrying out a deeper dive into understanding the nuances of these decisions.

Sometimes, I discover that an applicant found medical or respite care elsewhere, or perhaps succumbed to the severity of their ailment only a short while after the entry was created. Occasionally, I would allow myself a break from the reading and transcribing, as amongst the entries are so many intertwined social factors which reveal the harsh realities and dire circumstances numerous applicants would have faced. Then, there are the equally informative, contrasting entries concerning affluent applicants (usually with means derived from military or government posts).

Another interesting aspect of transcribing the casebook is discovering the existence of certain professions which have been replaced or become obsolete. In one entry, for example, the applicant has confirmed means via their father who is a “Cat’s Meat Seller”. This once-legitimate profession of door-to-door pet food sales is nowadays replaced by retail websites such as Zooplus. Further research led me down a rabbit hole on the trade of horse meat for domesticated cats. These details make imagining the lives of the applicants so vivid and interesting.

Occasionally, there are other historical surprises – there is one such applicant entry which inadvertently provided insight to a well-known historical figure, an artist, and their personal life. Further research revealed that the sister of the artist had an entirely different life, one with perhaps less autonomy due to the nature of her medical circumstances.

Life in and around London in the 1800s was a curious time, and there is so much I have enjoyed about transcribing the casebook. It has been a fascinating journey in developing my knowledge of medical history, the applicants who were supported by the RHN, and the magnitude of the impact of the RHN.

NJP

A Return to our Merrick Mystery:

Back in July, I wrote a short piece about the known-but-tenuous connection between the RHN and Joseph Merrick. This month, I want to go back to that mystery and talk more about where in our archives I have searched for answers.

To recap, on the 4th December 1886, Francis Carr-Gomm (then Chairman of the London Hospital) published an open letter in The Times newspaper appealing for help with Merrick’s case. At this point, the London Hospital (now The Royal London Hospital) had been caring for Merrick in a small attic room for a number of months. But the Hospital was not able to offer long-term care, and was seeking to place him elsewhere. In Carr-Gomm’s open letter, he stated that “The Royal Hospital for Incurables and the British Home for Incurables both decline to take him in”.

My goal, then, was to uncover evidence of this request and/or its rejection in the RHN’s archives. My first task was to determine the time span to research. From the date of Carr-Gomm’s letter, I already knew that any evidence would precede the 4th December 1886.

According to accounts of Joseph Merrick’s life, in 1885 he joined Sam Roper’s Travelling Fair, where he placed himself on public exhibition as one of their attractions. But this type of public spectacle – the ‘freak show’ of old – was already in decline and social reform, along with tighter policing, were precipitating its ultimate demise.

In a bid to salvage the deteriorating situation, Merrick travelled to continental Europe and embarked on a tour which proved equally disastrous. Sometime in early June of 1886, his then manager gave up on their enterprise and abandoned him in Brussels. Alone and destitute, Merrick pawned his few remaining possessions to pay his way to the coast at Ostend, where he was promptly refused passage aboard the cross-channel ferry due to his appearance.

Finally, on the 23rd June, he boarded a packet service from Antwerp to Harwich. Docking the following morning, Merrick caught an early train on to Liverpool Street Station in London. Malnourished and exhausted, he was rescued from a gathering crowd of onlookers by a policeman, who found Frederick Treves’s card on him. Treves worked a surgeon at the London Hospital, and a messenger was duly dispatched to fetch him.

In his published memoirs, Treves describes what happened next:

“I returned at once with the messenger to the station. In the waiting room I had some difficulty in making a way through the crowd, but there, on the floor in the corner, was Merrick. He looked a mere heap. It seemed as if he had been thrown there like a bundle… He seemed pleased to see me, but he was nearly done… The police kindly helped him into a cab, and I drove him at once to the hospital… He never said a word, but seemed to be satisfied that all was well.” [1]

Merrick was taken up to a single attic room which had once served as an emergency isolation ward. As Treves himself wrote retrospectively: “I had been guilty of an irregularity in admitting such a case, for the hospital was neither a refuge nor a home for incurables. Chronic cases were not accepted, but only those requiring active treatment, and Merrick was not in need of such treatment”. [2]

Based on the above data, I set a (generous) time span for my research of the 24th June (the date Merrick returned to England) to the end of December 1886 (allowing some time after the publication of Carr-Gomm’s letter for any response).

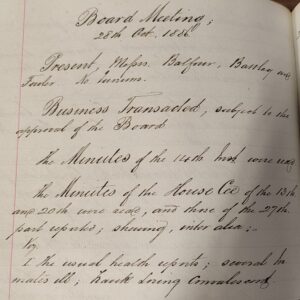

I started with the “Meeting minutes for the hospital board of management from 23 December 1884 to 12 May 1887” (GB 3544 RHN-AD-01-02-15). The Board met every fortnight to hear reports from the various heads of staff and departments. They discussed a variety of matters pertaining to staff and patients (such as health, holidays, visits, appointments, absences, and deaths); maintenance works; rule changes; financial income and expenditure; and any other business arising.

Fig. 5: Board Meeting Minutes 28th October 1886, (RHN-AD-01-02-15, p.371)

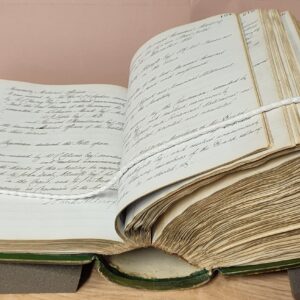

I turned next to the “Meeting minutes and reports of annual general meetings” (GB 3544 RHN-AD-01-01). This huge, unwieldy ledger contained only three sides of handwritten text which briefly summarised the year of 1886.

Fig. 6: Annual General Meeting Minutes, (RHN-AD-01-01)

Not hopeful, but wishing to be thorough, I trawled through the exhaustive weekly “Minutes of House Committee dating from 26 February 1896 to 10 March 1897” (GB 3544 RHN-AD-01-04-24). This revealed much about the everyday minutiae of life at the RHN in 1886 – fascinating in its own right – but nothing relating to Carr-Gomm’s published claim.

Fig. 7: Minutes of the House Committee, 21st July 1886 (RHN-AD-02-01-07, p.73)

I have no reason to doubt that Francis Carr-Gomm (or Frederick Treves) appealed to somebody at the RHN on behalf of Joseph Merrick. But that dialogue, and the decision to decline his case, seems to have taken place either behind closed doors or on an unofficial basis, and it there is no evidence of it amongst our surviving written records.

Dr Sarah E Hayward

References:

[1] Sir Frederick Treves, “The Elephant Man And Other Reminiscences” (Cassell and Company, Ltd., 1923), pp.11-12[2] Ibid., p.12

[3] Jeanette Sitton and Mae Siu-Wai Stroshane, “Measured by Soul. The Life of Joseph Carey Merrick (also Known as ‘The Elephant Man’)” (The Friends of Joseph Carey Merrick, 2022), p.57

Bibliography:

Peter Ford and Michael Howell, “The True History of the Elephant Man. The Definitive Account of the Tragic and Extraordinary Life of Joseph Carey Merrick” (Skyhorse Publishing, 2010)

Fig.8 Barrage balloons over London during WWII, unknown, 1939-1945

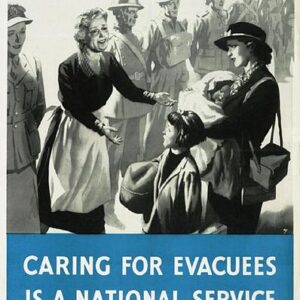

Fig.9 Poster issued by the Ministry of Health, 1939

Extracts from our minutes convey the process; including the Board asking provincial hospitals for any beds, the Matron taking a ballot of patients who wished to be evacuated, the Medical Officer preparing a list of patients who were unfit to be moved, and the Board making arrangements for the safety of the remaining patients and members of staff.

Extracts from Board minutes during August 1944:

“The Chairman informed the meeting of the offer made through the Ministry of Health Emergency Hospitals Service, Sector 8, for the evacuation of the Home to a distance from London. It was agreed, after discussion, that a further meeting should be held on Wednesday, the 9th instant, & that in the meantime, various Homes for Incurables in the provinces should be telegraphed, asking if they can take any of our patients as a temporary measure; that the Matron should take a ballot of the patients as to their wishes on being evacuated or remaining… It was also agreed that the Matron, in conjunction with the Medical Officer, should prepare a list of those patients, who, in their opinion, are unfit to be moved & who would probably suffer from the change.”

7th August 1944

“Particulars were given of the replies from the nine provincial Homes for Incurables which were asked by telegram if they could provide any beds. Seven of these Homes reported having no vacancies, one offered to provide twelve beds if four nurses & three domestics were sent, & the remaining Home offered to take in six women patients if one nurse & enough bed linen were supplied.

As the result of the Matron’s ballot of the patients showed that seventy-two (nine men & sixty-three women) wished to be evacuated, it was agreed, in order to avoid splitting up staff, to inform the Ministry of Health, Sector VIII, that the Home is prepared to accept their offer of evacuation. In addition to the seventy patients, twenty-two nursing & domestic staff, including a cook & three male attendants, would go with them.”

9th August 1944

“For the greater safety of the patients & in view of the depleted nursing & domestic staffs, the Board decided that it was expedient that all patients should be accommodated on the ground floor using both dining-rooms as dormitories, the North sitting-room, & two maids’ rooms in the basement, leaving the first floor absolutely vacant. In no instance can any patients be allowed to remain on the first floor.

The Chairman expressed his own & the Board’s gratitude to the Matron & the Steward for the parts played by them in the work of the recent evacuation of patients.”

23rd August 1944

We can only imagine the fear and logistical challenges that each individual faced, and we remember the bravery of our patients and staff during these demanding times, almost 80 years later.

Next month, we’ll be bringing you some yuletide pickings from our archives. We look forward to seeing you then!