I Only Have Eyes For You

Making a spectacle of ourselves for Valentine’s Day 2024

By Dr Sarah E Hayward, Edited: Craig Lloyd

Part of my work as a volunteer in the archives here at the RHN is cataloguing our collection of medical and scientific objects. With Valentine’s Day on the horizon, I thought I would share four items relating to the ‘windows to the soul’.

An ophthalmic eye speculum, circa early to mid-twentieth century

An ophthalmic eye speculum, dating from the early to mid-20th century, represents a crucial instrument in the history of medical advancements. This particular device is designed to retract the eyelids, facilitating various eye procedures, including cataract removal and laser eye surgery. Its design, while seemingly austere, plays a pivotal role in the realm of ophthalmic surgery, ensuring the patient’s eyes remain open and stable throughout the procedure.

The practicality and necessity of such a tool underscore its importance, transcending beyond its initial perception. While the application of an eye speculum might evoke discomfort at the thought, it’s imperative to appreciate its function within medical practice. It is a testament to the lengths to which medical professionals go to ensure the safety and effectiveness of treatments.

The use of an eye speculum, especially in historical contexts, also highlights the evolution of medical instruments over time. Despite its simple mechanism, the speculum’s design is still used today, but has been refined to minimise discomfort and maximise efficiency during surgery.

An optometry trail frame, circa mid-twentieth century

Our second object is a vintage example of a ‘trial frame’ – a tool with which many of you will be familiar – used by ophthalmologists and optometrists to test a person’s vision.

There are three slotted spaces (also known as cell or lens compartments) for different corrective lenses or other accessories to be placed before each eye. This means that spherical lenses to correct myopia (near-sightedness) or hyperopia (far-sightedness) can be layered with other corrective lenses to address astigmatism or alignment. An Occluder lens can also be used to block the vision entirely and thus test each eye in isolation.

The nose piece can be adjusted up or down, forwards or backwards, left or right, for comfort. There is no maker’s mark and we sadly don’t have the set of lenses which these frames are designed to hold.

A pair of high myopic glasses, circa mid-to late twentieth century

These pink framed glasses have unusually thick lenses with a distinctive central circular section. They are designed for high myopia, characterised by significant near-sightedness. High myopia is usually determined to require a prescriptive power of -6.00D or greater. The ‘D’ is the dioptre strength, which is the optical power of the lens.

We do not know who these glasses belonged to, but everyday domestic objects such as these serve to contrast the medical instruments with a more human and relatable perspective on our history.

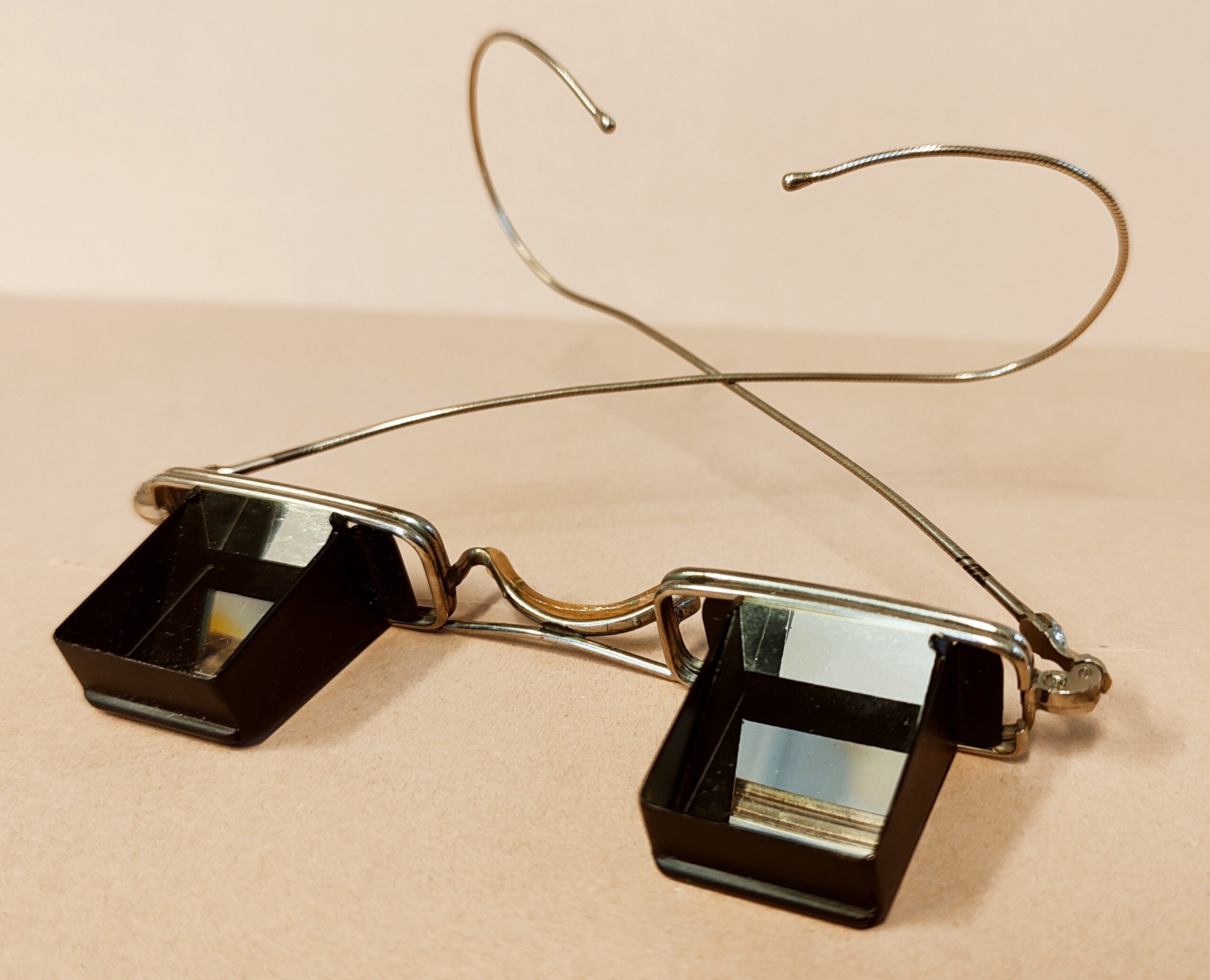

A pair of prism glasses, circa mid-twentieth century

These rather bizarre looking spectacles use angled prism lenses to shift the gaze by ninety degrees. This altered view allows a person to see horizontally when lying down flat (without the glasses on, you would be looking at the ceiling). From this position, you can comfortably read a book or watch the television without lifting your head.

Prism spectacles are still widely available – they are now often advertised as ‘lazy glasses’ – and are perhaps more relevant than ever in our age of ubiquitous screen use.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this optical insight into our collection!