Christmas at the ‘Home on the Hill’, 1913

Written by Dr Kirsty Walker

Fig. 1: The Home on the Hill by Bernhard Hugh in Our ‘at Home’, 1914, p. 34, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-2-3-22-2. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-22-pt2

Introduction

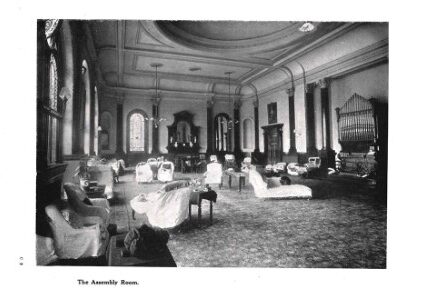

Special efforts are made at the Royal Hospital for Incurables at Christmas-tide. On Christmas Eve visitors came and sang carols to the patients. Then came Christmas Day with our Christmas services. The Assembly room was beautifully decorated with yule-tide and white flowers, &c. In the evening the nurses (who had been practising with Mr. Henniker, our Organist) sang carols. Light refreshments were provided for the patients, who afterwards retired to rest. [1]

What was Christmas like at the hospital over a century ago? An article from the Wandsworth Borough News, reprinted in the hospital’s annual Christmas fundraising appeal of 1914, gives us an extraordinary glimpse of Christmas day 110 years ago. From the festive decorations, gifts and carol-singing, to the Christmas dinner menu, entertainment and even a brief appearance by Father Christmas himself, it is remarkable how many of the traditions we value today were well established by the early twentieth century.

The Home on the Hill

Situate [sic] on West-hill, Putney, almost within a stone’s-throw of Putney Heath, on the brow of a hill, and in its own grounds, which comprise some twenty-four acres, this national institution is a landmark for miles around. And what a welcome awaits you as you enter its entrance hall, with the lofty wards and corridors, and spacious rooms opening all around you. How pleased the Patients are to see you; even the bashful visitor is soon at his ease, conversing with first one and then another Patient, until it seems as if it cannot be the first visit, but the fiftieth.[2]

Fig. 2: The Royal Hospital & Home for Incurables, Putney, c.1907-1922, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-PH-01-01-0010-01. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-ph-01-01-0010-01

In 1913 the Royal Hospital for Incurables, as it was then called, was home to 235 patients.[3] The admission case books allow us to identify some of the patients who could have been present on Christmas day.[4] Some were long-term residents. They suffered from a wide range of chronic conditions, often affecting their mobility, including paralysis, gout, chronic rheumatism, and spinal disease. From their applications, they had enjoyed previous economic security, often in skilled trades. Among these patients were a former hospital nurse, a domestic servant, a shop assistant in a milliner’s shop and a teacher. Unable to work due to poor health, they survived on meagre savings and occasional odd jobs. Most relied on family or friends for financial support, until they were admitted to the hospital to be cared for, for the rest of their lives. Elizabeth Bedford had been accepted for election as an Inmate at the hospital in 1895 with a compound fracture of her left femur after a railway accident. Before her accident, she had worked at Farringdon Street Station. Due to her injury she was dependent on her sister and brother-in-law who was a journeyman smith. In 1913 she would have been 63, and had been resident in the hospital for 18 years. She remained at the hospital until her death in November 1923.[5]

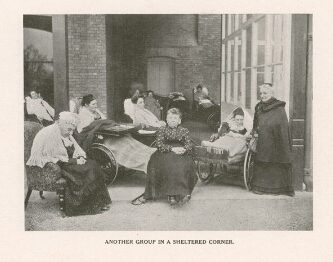

Fig. 3: Another Group in a Sheltered Corner in Not Abandoned, 1910, p.24, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-02-03-16, https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-16

To Elizabeth, and many other patients, the hospital was their home. Recognising this, hospital staff worked hard to mark significant occasions like Christmas.

Hark, the herald angels sing!

“Hark, the herald Angels sing! Glory to the new-born King.” These joyous words of the Christmas carol and many other familiar ones would have been heard on Sunday evening, the 21st December, as the nurses, assisted by members from the Parish Church and Trinity Church choirs, went round the wards, under the direction of the organist, singing Christmas carols to the Patients who had already retired for the night, and with this, Christmas at the Royal Hospital for Incurables may be said to have begun.[6]

In the days before Christmas, the rooms and wards were “tastefully decorated with holly and evergreens” by the nurses. While artificial Christmas decorations were starting to arrive on the market by the late nineteenth century, traditional evergreen decorations which had been used to mark the winter solstice for centuries, remained popular. The use of holly, ivy, mistletoe and fir in garlands and wreaths, blended with Christian symbolism of eternal life and rebirth, and in the early twentieth century it was common to see homes and churches decorated in this way.

Fig. 4: A Welcome Visitor by Bernhard Hugh in Our ‘at Home’, 1914, p. 28, RHN/FU/02/03/22/2, https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-22-pt2

Patients received cards and gifts from friends and family, and many were “cheered by the receipt of some useful article or garment”. By the end of the nineteenth century the practice of sending Christmas cards and exchanging gifts had been firmly established as British Christmas traditions, as manufacturers and shopkeepers capitalised on their commercial possibilities. The matron, Miss Lucy Begg, presented each patient with a bottle of sweets. Donors and patrons of the hospital also sent gifts for the patients. Mr and Mrs Leslie of South Croydon, who were regular donors to the hospital, sent a silver teaspoon to each female patient, and a packet of tobacco to each male patient.[7]

At 7.15 on Christmas morning, the nurses sang Christmas hymns in the wards before starting their duties for the day. This was followed by a service in the assembly room led by the Chaplain, Reverend Digby Gritten, with 90 patients receiving the Holy Communion.

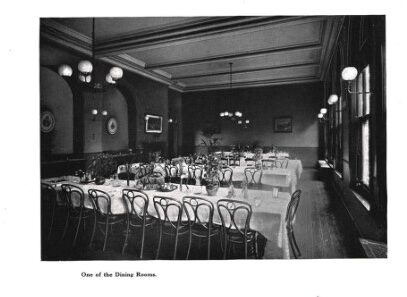

Fig. 5: One of the Dining Rooms in My first year in the Royal Hospital for Incurables Putney Heath by a patient, 1907, p.13, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-02-03-14. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-14

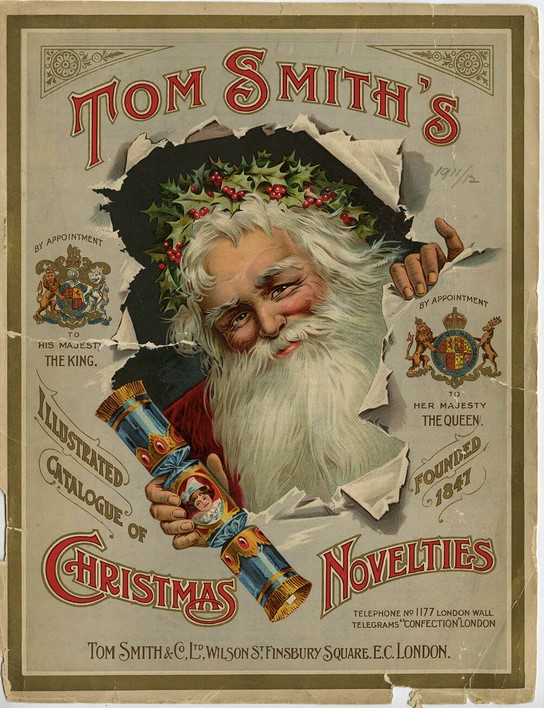

After the service, everyone adjourned to the dining rooms, where the Christmas fare consisted of “roast turkey, plum pudding, cheese, celery, and dessert of all kinds.” Until the early twentieth century, turkey was the Christmas dinner of the wealthy but as turkeys became cheaper to rear and so less expensive to buy, they began to be found more commonly on the Christmas dinner table. During dinner, patients and staff pulled crackers “containing caps, masks, and various articles of adornment”. Crackers were also a fairly recent addition to Christmas celebrations. They were invented by Tom Smith, a confectioner and baker in London in the 1840s and marketed for use at a wide range of celebrations. But by the end of the century they had adopted the modern form with the twist of wrapping, the ‘crack’ mechanism, a small note, paper hat and trinkets, and began to be manufactured at scale.

Fig. 6: Decorative box lid for Tom Smith’s Christmas Crackers from 1911, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tom_Smith_Christmas_crackers_1911.jpg

The Christmas entertainment

The climax was reached when at six o’clock in the evening the assembly room was crowded to its utmost, for the nurses then gave their fifth annual Christmas entertainment to the Patients. This is the one event in the year in which every Patient endeavours to do honour to his or her nurse, in spite of pain and suffering, for the nurses had for the last two months devoted all their spare time to rehearsing, in order to make the entertainment a huge success.[8]

Christmas day ended with an evening programme of musical and dramatic entertainment performed by the nurses, and arranged by the organist and a patient, Frederick Winter. He had been admitted to the hospital 8 years earlier with paraplegia.[9]

Fig. 7: The Assembly Room in My first year in the Royal Hospital for Incurables Putney Heath by a patient (1907), p.5, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-02-03-14. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-14

The show began with a musical prologue sung by nurses dressed in costumes of red, white and blue. As the chorus sang ‘Hail! Christmas, hail!’, Father Christmas made his appearance, impersonated by Attendant R. Robertson. By the turn of the twentieth century, the modern figure of Father Christmas that we would recognise today, synonymous with gift-giving, the iconic red suit and white beard had become deeply-rooted in British popular culture. Then followed an eclectic programme of stirring British patriotic songs, moving Irish ballads, comical poems and contemporary music-hall favourites, including:

- Land of Hope and Glory (1902), by English composer Edward Elgar and A.C. Benson

- The Meeting of the Waters (1808), The Minstrel Boy (1813), and The Last Rose of Summer (1813) popular folk-songs by Irish romantic poet Thomas Moore

- Gretchen, Madchen, Mine; The Song of the Old Dutch Mill (1907), by American song-writer John Golden

- Aunt Tabitha (1871-72), a poem by American poet Oliver Wendell Holmes

- The Old Cracked Basin (1907), a music-hall song by English writer T.W. Connor

- Auld Lang Syne (1788), based on the poem by Robert Burns

- I don’t want to play in your yard (1895), an American music-hall song written by Philip Wingate and Henry Petrie

The nurses’ performances were followed by an entertaining marionette show by Mr Winfield White, who called himself “The Living Marionette Entertainer with the Human Brain”.[10] By the early twentieth century, marionette shows were no longer the popular form of entertainment that they had been in Victorian Britain, but some well-known family troupes still travelled the country presenting shortened versions of the latest popular entertainment.

Fig. 8: Suffragettes – London – Arrest of Suffragette – Oct. 1913, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suffragettes_-_London_-_Arrest_of_Suffragette_-_Oct._1913_LCCN2003653981.jpg

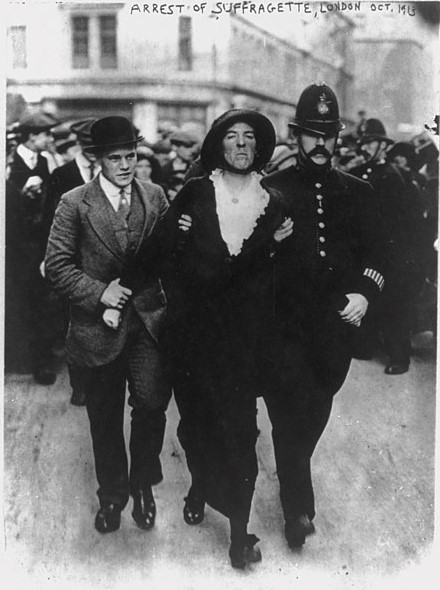

The programme concluded with a humorous sketch entitled ‘The Woman’s Rights Association’. The characters included ‘Miss Jemima’ (president), ‘Miss Prim’, ‘Miss Green’ ‘Miss Pure’, ‘Miss Handy’, and ‘Mrs. Blunt’. The scene was set in Miss Jemima’s drawing room, and the “amusing sketch went with a breeze from start to finish”. In 1913, the suffragette movement in England was at its peak, as women campaigned vigorously for the right to vote. Suffragette actions had become more militant, involving direct action and civil disobedience. It is possible that this sketch was influenced by the suffragettes’ increasingly violent struggle for women’s rights.

After a rousing rendition of the national anthem, the patients adjourned to the dining rooms “where tempting edibles were awaiting consumption”, and the day finally came to an end.

Conclusion

The following years would be difficult ones for the hospital with the outbreak of the First World War just eight months after the scenes described here. Attendants and nurses left, volunteered, or were conscripted; some never returned. But while this decade of life in Britain would become a tumultuous one, as John Millar, the steward, declared in his closing speech: “Christmas Day at the Institution had been a very happy one, both for patients and staff, from beginning to end”.

References

[1] My first year in the Royal Hospital for Incurables Putney Heath by a patient, 1907, pp. 10-11, RHN Archives, GB 3544 RHN-FU-02-03-14. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-14

[2] Our ‘at Home’, 1914, p. 34, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-2-3-22-2. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-22-pt2

[3] Our ‘at Home’, 1914, p. 41, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-2-3-22-2. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-22-pt2

[4] See for example: Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0737; Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0881; Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0543; Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0622; Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0770; Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0076; Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0137.

[5] Case Book, Volume 9, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-9-0737. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-ad-02-01-9-0737

[6] Our ‘at Home’, 1914, p. 35, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-2-3-22-2. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-22-pt2

[7] ‘Happy Incurables’, Wandsworth Borough News, p. 7.

[8] Our ‘at Home’, 1914, p. 37, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-FU-2-3-22-2. https://archives.rhn.org.uk/index.php/rhn-fu-02-03-22-pt2

[9] Case Book, Volume 11, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-11-0647.

[10] Advertisement, The Stage, 22 August 1922, p. 17.